Studies estimate that the Arctic could witness its first ice-free summer as early as the 2030s. This anticipated change may potentially ease access to the region’s abundant natural resources, including oil and gas, rare earth metals, marine livestock, and other Arctic minerals such as copper, zinc, coal, etc. Simultaneously, it may also open up new maritime routes in the region. Amidst these developments, a critical question arises: Who or what governs the Arctic region?

A common narrative suggests that akin to its counterpart, the Antarctic, the Arctic is a Global Common—a resource domain not falling within the jurisdiction of any one particular country, to which all nations have access. If this were true, we could have been witnessing an unprecedented race among nations to establish dominion over the region, much like the one we are likely to witness in space in a few decades.

This, however, is not exactly the case. To understand why, we need to understand its geography.

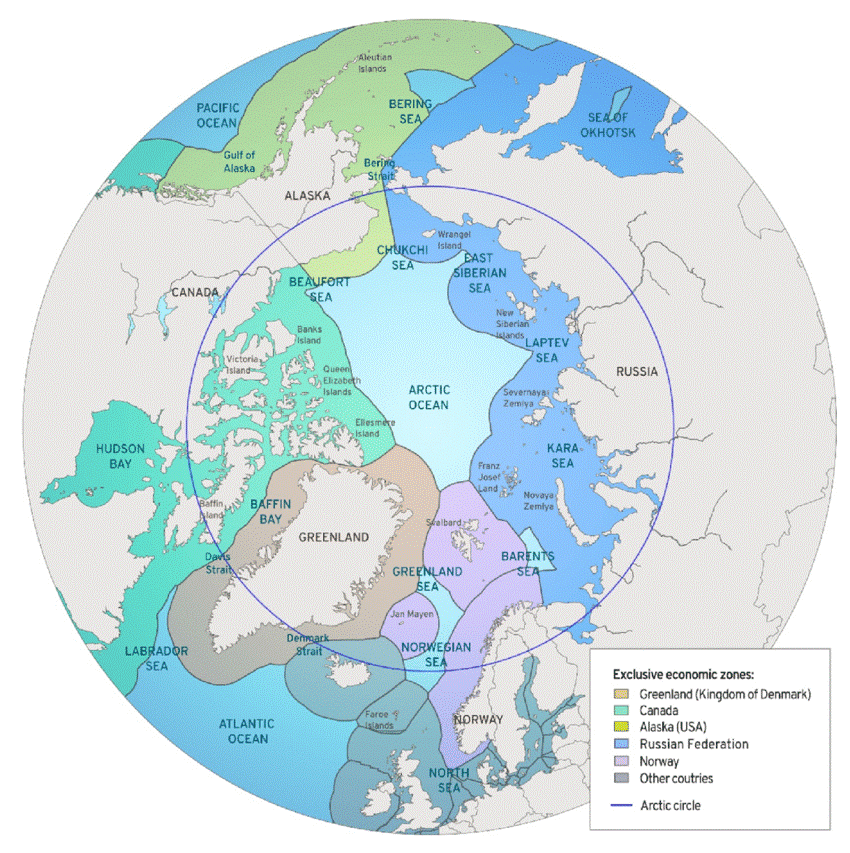

As can be observed in the above map, the Arctic region consists primarily of three key components:

- The Arctic Ocean

- The land territories of the Arctic states

- The sea territories of the Arctic states

The Arctic Ocean, recognised as the world’s smallest and shallowest ocean, is surrounded by five countries—Canada, Denmark (Greenland), the United States (US), Russia, and Norway, as depicted in the map. The countries are often referred to as the Arctic coastal states.

UNCLOS

The distinct coloured areas surrounding each country in the above map represent their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). As per the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the EEZ constitutes the zone where the coastal country possesses certain rights, duties, and jurisdiction. This encompasses activities such as the exploration and exploitation of natural resources, power generation through wind and water, fishing, amongst others. Under Article 57 of the convention, this zone stretches up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline used to measure the breadth of the territorial sea. Beyond the 200 nautical miles from the coast of these states remains a triangle-shaped region, referred to as the Central Arctic Ocean (CAO) or simply the Arctic High Seas.

Adhering to international law in this case was advantageous to these countries as it allowed them to have control over a substantial area of the Arctic Ocean with minimal territorial conflicts.

Under the UNCLOS, these high seas are indeed a global common, the common heritage of mankind. Accordingly, all countries have certain inherent rights in these high seas, covering resource exploration and exploitation, fishing, scientific investigation, the right of navigation, and more.

Considering their national interests, the Arctic coastal countries jointly declared in 2008 that the Law of the Seas would be the appropriate framework to govern the Arctic region. Adhering to international law in this case was advantageous to these countries as it allowed them to have control over a substantial area of the Arctic Ocean with minimal territorial conflicts. Since the Arctic region comprises the land territories of Arctic states, maritime zones of Arctic coastal states, and the high seas, the region could very well be dubbed as a “Quasi-Global Common”.

Governance: The Arctic Council

Due to the peculiar conditions, inhospitable nature, and general lack of state assets and capabilities in the region, the Arctic necessitated a novel governance structure. To this end, under the Ottawa Declaration of 1996, the Arctic Council was established as a high-level intergovernmental forum by the Arctic States—the five Arctic coastal states plus Sweden, Finland, and Iceland.