India targets net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, says Modi

India’s economy will become carbon neutral by the year 2070, the country’s prime minster has announced at the COP26 climate crisis summit in Glasgow. The target date is two decades beyond what scientists say is needed to avert catastrophic climate impacts. India is the last of the world’s major carbon polluters to announce a net-zero target, with China saying it would reach that goal in 2060, and the United States and the European Union aiming for 2050.

COP26: What climate summit means for one woman in Bangladesh

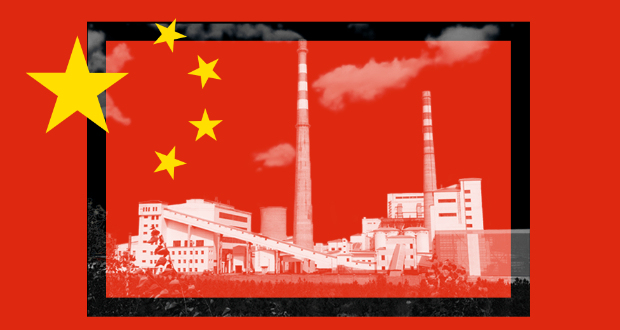

China's carbon emissions are vast and growing, dwarfing those of other countries. Experts agree that without big reductions in China's emissions, the world cannot win the fight against climate change. In 2020, China's President Xi Jinping said his country would aim for its emissions to reach their highest point before 2030 and for carbon neutrality before 2060. His statement has now been confirmed as China's official position ahead of the COP26 global climate summit in Glasgow. But China has not said exactly how these goals will be achieved.

Why China's climate policy matters to us all

China's carbon emissions are vast and growing, dwarfing those of other countries. Experts agree that without big reductions in China's emissions, the world cannot win the fight against climate change. In 2020, China's President Xi Jinping said his country would aim for its emissions to reach their highest point before 2030 and for carbon neutrality before 2060. His statement has now been confirmed as China's official position ahead of the COP26 global climate summit in Glasgow. But China has not said exactly how these goals will be achieved.

Deliver on promises, developing world tells rich at climate talks

A crucial U.N. conference heard calls on its first day for the world's major economies to keep their promises of financial help to address the climate crisis, while big polluters India and Brazil made new commitments to cut emissions. World leaders, environmental experts and activists all pleaded for decisive action to halt the global warming which threatens the future of the planet at the start of the two-week COP26 summit in the Scottish city of Glasgow on Monday. The task facing negotiators was made even more daunting by the failure of the Group of 20 major industrial nations to agree ambitious new commitments at the weekend.