The blame for starting the conflict falls squarely on Putin, who decided to invade his neighbor. Nevertheless, allied officials created the incendiary circumstances which led to the war. Indeed, Western leaders well understood that their aggressive policies after the Cold War made confrontation likely.

For instance, in 2008 the George W. Bush administration pressed its allies to expand NATO to Georgia and Ukraine. National intelligence officer Fiona Hill, who later served on the Trump National Security Council staff, briefed Bush, predicting “that Mr. Putin would view steps to bring Ukraine and Georgia closer to NATO as a provocative move that would likely provoke pre‐emptive Russian military action.” William Burns, Bush’s ambassador to Russia and President Joe Biden’s CIA director, sent a famous cable warning the administration that “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin).” Such a step would “create fertile soil for Russian meddling in Crimea and eastern Ukraine.”

The stakes were evident when Putin expanded military forces along Ukraine’s border in late 2021. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg admitted: “The background was that President Putin declared in the autumn of 2021, and actually sent a draft treaty that they wanted NATO to sign, to promise no more NATO enlargement. That was what he sent us. And was a pre‐condition for not invade [sic] Ukraine. Of course we didn’t sign that.… So he went to war to prevent NATO, more NATO, close to his borders.”

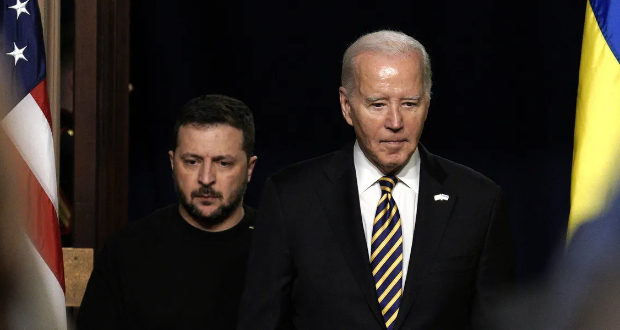

In March 2022, even Zelensky acknowledged as much: “Security guarantees and neutrality, the nuclear‐free status of our state. We are ready to agree to it. This is the most important point. This was the first fundamental point for the Russian Federation, as far as I remember. And as far as I remember, they started a war because of this.” Yet the U.S. helped torpedo Russo–Ukrainian negotiations.

The continuing war is an obvious disaster for the participants, most importantly Ukraine, since it provides most of the battlefield. Blustery predictions in late 2022 and early 2023 that Ukraine could liberate the Donbass, retake Crimea, push Putin from power, force regime change in Moscow, and perhaps even break up the Russian Federation are now long‐discarded fantasies. Wistful hopes that the Zelensky government can rebuild for a renewed offensive next year seem unrealistic in view of Ukraine’s serious manpower shortage, which has led to draconian conscription measures.