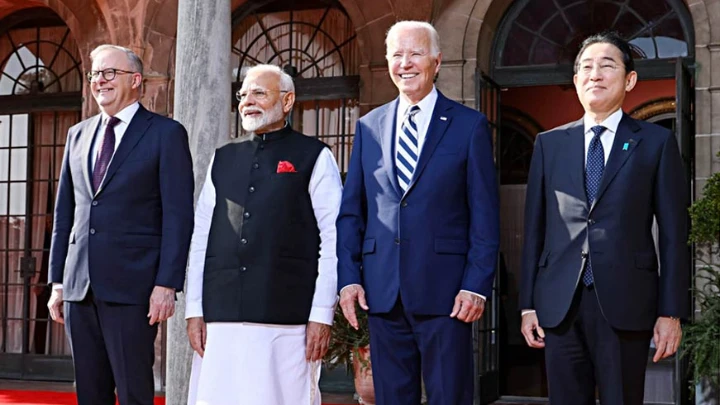

When United States (US) President Joe Biden welcomed the Prime Ministers (PM) of India, Australia, and Japan to his hometown of Wilmington for the fourth in-person Quad Leaders’ Summit last week, the mood was one of high optimism. The summit marked a farewell for both Biden and Japan’s PM Fumio Kishida, and President Biden seemed eager to make it count. Two years after Quad’s formalisation, the commitment to regional cooperation was unmistakable, and Biden was determined to build on the momentum.

The gathering hit all the right notes on Indo-Pacific security, with leaders voicing concerns about the “militarisation” of contested territories and “coercive and intimidating manoeuvres” in the South China Sea. Though China wasn’t mentioned by name, the references were clear.

The summit’s declaration was detailed and comprehensive, listing a wide range of cooperation initiatives, including a cancer moonshot, the maritime training initiative in the Indo-Pacific, the Quad-at-Sea Ship Observer Mission, a Quad Indo-Pacific logistics network, an expanded infrastructure initiative, and the Quad Bio-Explore project. It gave the impression of a united grouping moving in strategic unison.

Countries in the region, particularly in South Asia, remain hesitant to share sensitive information, largely due to concerns over foreign commercial satellite services, which they fear may infringe on their national sovereignty.

Yet, if one were looking for clarity on Quad’s specific trajectory and tangible outcomes from its initiatives, one is likely to be disappointed. Despite the rhetoric, much of Quad’s military objectives remain vague. Take the Quad Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness initiative. While it has found some success in the Pacific, practical achievements, especially in the Indian Ocean, have been minimal. Countries in the region, particularly in South Asia, remain hesitant to share sensitive information, largely due to concerns over foreign commercial satellite services, which they fear may infringe on their national sovereignty. Differing legal frameworks, limited technological infrastructure, and the absence of clear protocols for accessing satellite data continue to hinder practical cooperation.

While Quad did subtly criticise Chinese violations of international law and unilateral actions in the East and South China Seas, it failed to address the larger issue of US distraction. With the US deeply involved in Ukraine, it has limited resources left to confront China. Though Washington acknowledges Beijing as a threat to Taiwan and a growing concern in both the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, it is far from prepared to challenge China, especially in the latter region, where no clear US maritime strategy exists.